April 3, 2013

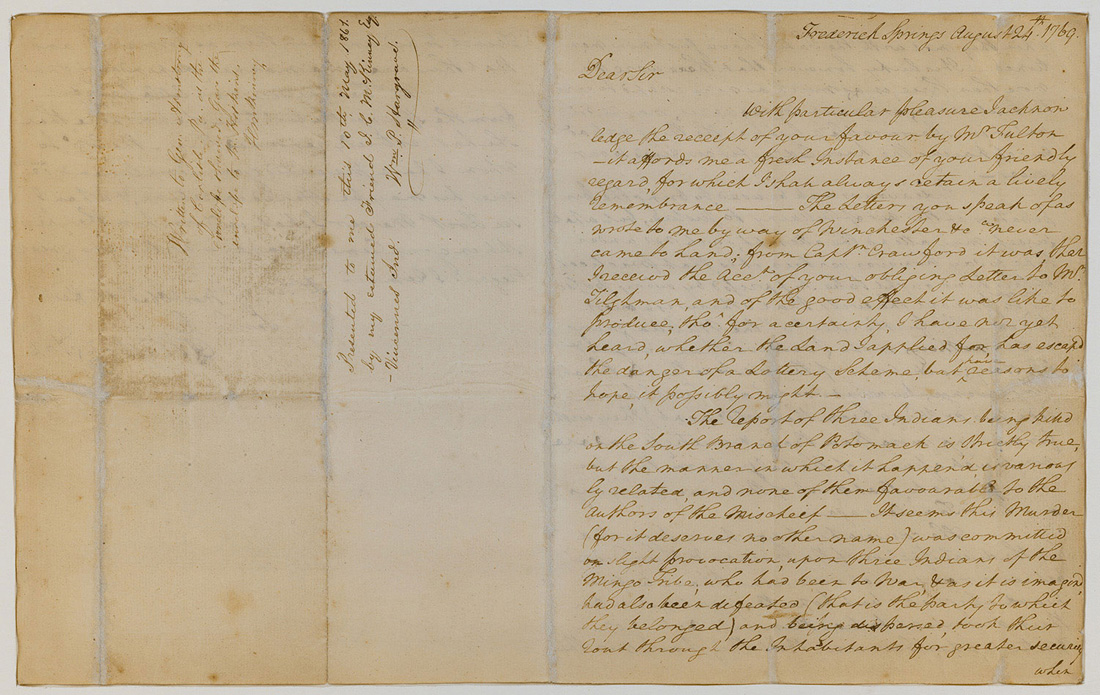

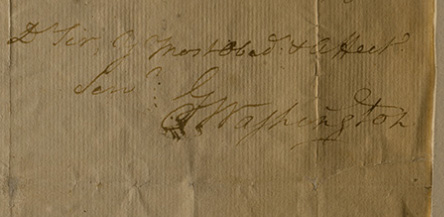

Due to the generosity of Mr. Barron Kidd of Dallas, Texas, the Briscoe Center has acquired a letter written by the first president of the United States, George Washington. The Briscoe Center’s letter discusses the murder (“for it deserves no other name”) of three members of the Mingo Indian tribe by white settlers on the south bank of the Potomac. The letter sheds light on Washington’s views on Indian relations, his moral character and his acute awareness of the public sphere.

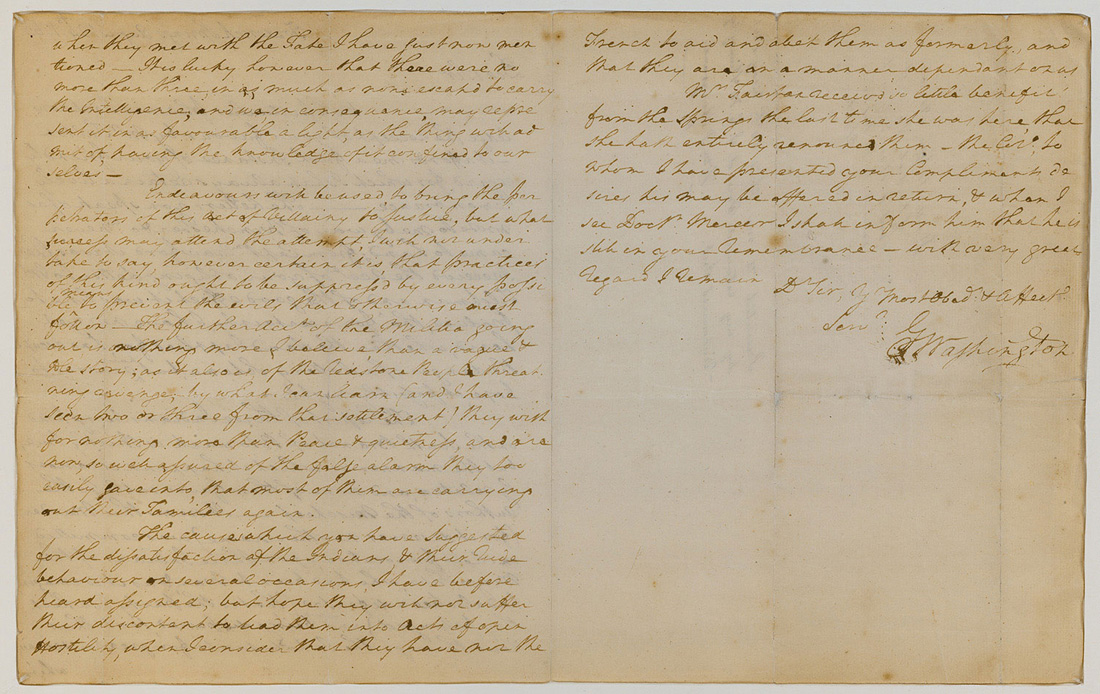

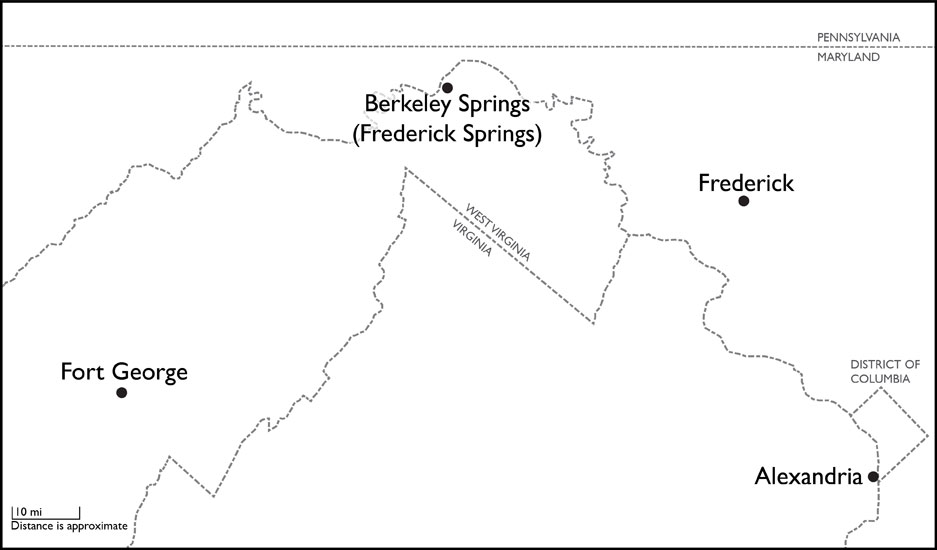

The Briscoe Center’s letter was written to John Armstrong on August 24, 1769. It finds Washington between wars, actively pursuing his financial and domestic interests. During the period of time between his marriage in 1759 and the start of the Revolutionary War in 1775, Washington lived a busy life, serving as a vestryman and as a member of the House of Burgesses in Williamsburg, purchasing land and managing his plantations.

Armstrong was an Irish immigrant who worked as a land surveyor in Pennsylvania as well as serving as a justice of the peace. Armstrong advised Washington about dealing with the Land Office in Carlisle, Pa., while obtaining land grants and on developments in local relations with Indian tribes. (Later, he would serve as a major general under Washington in the Revolutionary War.)

By 1769, Washington was in the midst of considerable efforts to expand his land holdings to the west, especially into what was called “the Ohio Country” (made up of what is now Ohio and parts of Pennsylvania and West Virginia). It is understandable that both Washington and Armstrong had a vested interest in any developments in that region that might indicate serious trouble with the Indians and therefore inhibit western expansion by colonists.

“… the manner in which it happen’d is variously related, and none of them favourable to the authors of the Mischeif …”

Washington relays the information he has on the incident to Armstrong, along with his thoughts on the matter. According to Washington’s intelligence, the three Indians were returning from “war” — probably a war party or raid against other Indians — and traveled “through the Inhabitants” to be safe from further attacks.

Washington describes the incident as “murder,” “villainy,” and “mischief.” He demands “justice” and calls for such incidents to be “supressd.” His indignation is also driven by a fear of “the evils that otherwise must follow” if similar incidents were to go on unchecked and with increasing frequency.

It is interesting to note that Washington demonstrates a keen awareness of colonial Virginia’s public sphere: “It is lucky however that … none escapd to carry the Intelligence, and we, in consequence, may represent it in as favourable a light, as the thing will admit of, having the knowledge of it confined to our selves.” Washington obviously understood the destabilizing effect on communities that rumors of souring Indian relations could bring.

Washington’s attitudes appear to be in line with those of his peers. During an Aug. 8, 1769, meeting, the Council of Colonial Virginia notes that:

“no injury or violence be offer’d to the Indians; and if hereafter it should become a serious business proper measures may be taken for the defence of the Inhabitants, who should be caution’d that if they wantonly draw on a quarrel with the Indians, they will not be supported by Government.”

Washington sincerely believed that, “the Redstone People … wish for nothing more than Peace & quietness.” At the same time, avoiding open hostility with Indians was in the interests of ambitious landowners such as Washington and the men of the Virginia Council. No doubt the council joined Washington in hoping that the Indians “will not suffer their discontent to lead them into Acts of open Hostility.”