Photographer Fred Baldwin (1929-2021) wrote this essay on his experiences in Afghanistan in 1966 as part of his service in the Peace Corps. In both words and pictures, Baldwin documented the establishment of medical clinics in Jalalabad. The Briscoe Center is home to the archives of Baldwin and Wendy Watriss, which include their individual and collective work as documentary photographers, writers, journalists, exhibition curators and organizers of FotoFest.

This story describes a time when I joined thousands of other Americans, both young and old who accepted of President Kennedy’s challenge: “Ask not what your country can do for you but what you can do for your country.”

In the summer of 1966, I finished my two year tour as Peace Corps Director in Sarawak (East Malaysia) and was returning home to resume my career as a photojournalist. I was asked by Peace Corps Washington to detour to Afghanistan to document a new experimental grass roots program in Jalalabad to introduce Peace Corps volunteer medical professionals and their families, to address community health needs.

A two-day bus ride from New Delhi to Kabul took me through Pakistan until we reached a serpentine road, with special lanes for camels, climbing from the flat plains of the Punjab in Pakistan to 3,500 feet. We drove through the Khyber Pass, described by Rudyard Kipling as a “sword cut through the mountains.” The jaws of rock served those who controlled it giving them the power to levy a price on all who chose to make the passage. It joined one world to another and helped shape centuries of history – battles, ambushes, and blood spills.

The Pashtun lived on both sides of this geological gap and defended it successfully from the most powerful armies of the time. Invaders from the time of Alexander the Great in 326 BC, followed by Genghis Kahn, Tamerlane and the Moguls who established their dominance in 1526 had come from the west. Coming from the east, the British had attempted to invade from India, using the Khyber to subdue Afghanistan in three wars starting in 1839 and ending their final effort in 1919.

As the road passed an old stone fort at Ali Masjid, we stopped at an eerie spot that had a dozen or more tombstone-sized regimental seals dedicated to soldiers who had served in the Khyber during the 19th and 20th centuries. One of these shields represented a unit of 5,000 British and Indian troops and 12,000 camp followers who attempted to withdraw to India from Kabul in 1841. Here, on this same pass in freezing weather, the fierce local tribesmen created a deadly trap that resulted in a military disaster for the Raj. Only one survivor, a British military doctor, made it back to Jalalabad.

Landi Kotal, a village at the top of the pass, just a few miles from the Afghanistan border, we disembarked and were immediately surrounded by villagers selling locally made souvenirs; including fake Lee Enfield rifles, the iconic weapon that the British had used during two World Wars. Guns were the local cottage industry. They seemed well made, with stamped serial numbers, but the Colt revolver with the Ɔ stamped backwards was probably not manufactured in Hartford, Conn.

We followed this truck at the border crossing into Afghanistan. Dozens of people jammed inside a vehicle designed to seat six, clinging to ladders or bumper. Men hung like fruit from a tree. Others perched among huge sacks on top.

As we swerved around another hairpin curve, a solitary Pashtun tribesman, turbaned and draped in layers of baggy clothing came into view. He, like many others had a Lee-Enfield military rifle slung over his shoulder.

Tunnels had been bored through the mountains to ease the passage. They were mysterious rat holes from the distance and when the bus reached them, we plunged. There was momentary blindness, a few seconds of complete blackness, then brilliant daylight framed more mountains in a black semi-circle as the bus rushed to meet another spectacular view.

The area was both menacing and exhilarating, filled with the grim ghosts of a violent past. It was very male. There was nothing in sight that balanced the rugged landscape or softened the sharpness of the jagged, twisting route of the Khyber Pass. During their third Afghan war in the early 19th Century, a British soldier had written: “Every stone in the Khyber has been soaked in blood.”

All along the route we followed trucks with decorations that enlivened the most boring stretches of road. Each truck was different – personalized to the taste of the driver. To get stuck behind these vehicles was a pleasure. They were mobile museums of brightly colored folk art – that seemed wildly inappropriate to arid Afghanistan: steamships, jet aircraft, ancient sailing vessels, beautiful birds. There was even a red double-decker London bus, along with the Taj Mahal painted on one truck. The trucks were mobile bouquets of individuality that added a cheerful accent to the grim surroundings.

My favorite was an elaborate white winged horse with a woman’s face was painted above the cabin of one truck. This was Buraq, the celestial magical steed with wings of an eagle and the tail of a peacock that had taken the prophet Mohammad from Mecca to Jerusalem, as well as a side trip to Heaven and a visit to the prophets, Jesus, Moses and Abraham. He was advised by Allah to tell the people to pray to Him five times a day. Then with a few more strides on the back of Buraq, Mohammad was dispatched back to Mecca. No wonder Buraq was so popular with truck drivers.

Jalalabad was protected from freezing temperatures and dust choking winds in November by the Safed Koh Mountains, but in the late days of September when I arrived, it was still hot. The waters of the Kabul River made it a relatively fertile plain. Citrus fruits, date palms, and sugar cane as well as cereal crops dotted the grey expanses of flatness leading up to the nearby jagged mountains. As Afghanistan’s second city, Jalalabad had been an important commercial center, where, for centuries, trade had passed between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

I arrived to meet a traffic jam in Jalalabad — sardine packed busses, camels bearing huge loads were led through the confusion. Carts assembled from junk automobile axles, provided mobility. Long walks in Jalalabad helped me adjust to the new experience. The few women I saw were being taxied in by horse drawn carts. They were all dressed in the traditional chador which covered them from head to toe. A square opening, embroidered with a lacy grill, allowed them to see.

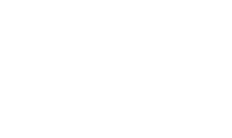

Picture taking was easy with my inconspicuous Leica, and there were no tourists. “Where do you come from?” was a common question. Men asked me to take their picture. Every man was wearing headdress that represents his tribe. The Turban, known as a lunge, was warm in the winter and kept the brain cool during the intense heat of the summer.

The scarf-like piece of fabric was light, breathable cotton and a short length that escaped from the side could be used to shield the face from high velocity winds propelling sand and dirt. The pakol, a soft round beret-like hat with copious amounts of wool rolled up made a bulging sausage shaped rim around the hat, could be pulled down to shield the neck and face from the cold. This is the hat worn by Pashtun tribes who dominated the area on both the Pakistan and Afghanistan sides of the Khyber region.

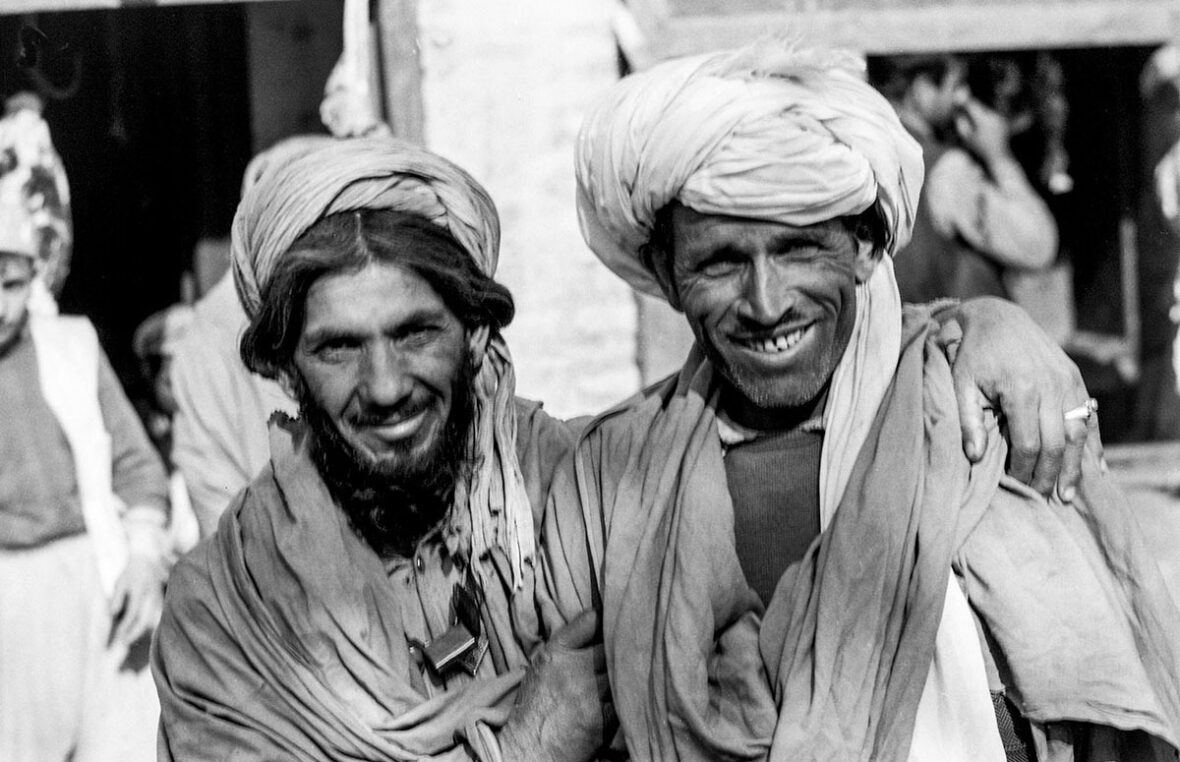

An old man seemed pleased by my wanting to photograph him with his camel. His biblical look charmed me. Unable to say “thank you” in Farsi, Dari, Pashtu, Turkmen, or Uzbek, I rewarded him with a big smile, which seemed to be acceptable currency.

One of my explorations of Jalalabad took me onto a long bridge that passed over the Kabul River. In the late afternoon I saw six laden camels silhouetted against the low light in a natural theater that changed as the shadows grew longer and longer. People and animals no longer seemed real — abstracted against the dimming ball of the setting sun.

It was Ramadan, the holiest period in Islam, the ninth month in the Islamic calendar that began as the new moon appeared in sky — a period of fasting and religious reflection that lasted from dawn until the sun set. It was also a period of extreme stress as workers carried on, not only without food but also without water. The fast was mandated for everyone with the exception of pregnant women, lactating mothers, small children, and the old and infirm.

One of the Peace Corps doctors, Dennis Hamilton, took me to a place where the arrival of dusk allowed men to break their fast with tea and saffron flavored rice with shreds of lamb. Dr. Hamilton explained that Ramadan fasting had spiritual aspects that transcended appetite. It was a temporary social and cultural equalizer that gave the devout a special perspective that connected all practicing believers — those who were fortunate to be full bellied and those who were not. During this special time they shared a deeply felt common experience that bonded them in the most visceral way through hunger and thirst. The religious ritual was relevant to the lessons that I had learned from hunger and thirst in mountains of Korea in 1950 -51 that I shared with fellow Marines.

The teahouse was filled with rough, turbaned, dusty tribesmen seeking relief from a world outside that was harsh enough without fasting. Afghanistan is a land of extremes. The proximity of the mighty Himalayas and the desert winds supplied a blow torch of scorching heat in summer and biting cold in winter.

Alcohol and women were absent in this dark and crowded public space. A single stovepipe angled up from a wood-burning stove in the middle of the room and even with the help of hot tea, nobody shed their warm clothes.

A poster featured two wrestlers. They were bare-chested and burly, wearing tight wrestler’s shorts. Super-manhood, strength, and was delivered in the style of the most exuberant truck art.

Then, two dancers appeared in the middle of the crowd, young boys wearing women’s headscarves rose and began swaying, rotating, and undulating their bodies. They were bacha bazi, or Dancing Boys. Their lifted arms waved to the music in erotic ways. The men watched the teasing dancers calmly.

As sex among men is high on the forbidden list in conservative Afghanistan, I was amazed to witness this seemingly provocative performance. Perhaps it went back to the tradition of men portraying women in the theatre of the Ancient Greeks or like my boarding school, St. Marks where members of the all-male student body took women’s parts in a school play. And yet again, it seemed strange that this form of teasing entertainment fitted into such a profoundly masculine culture bound to the well-known prohibitions of Islam.

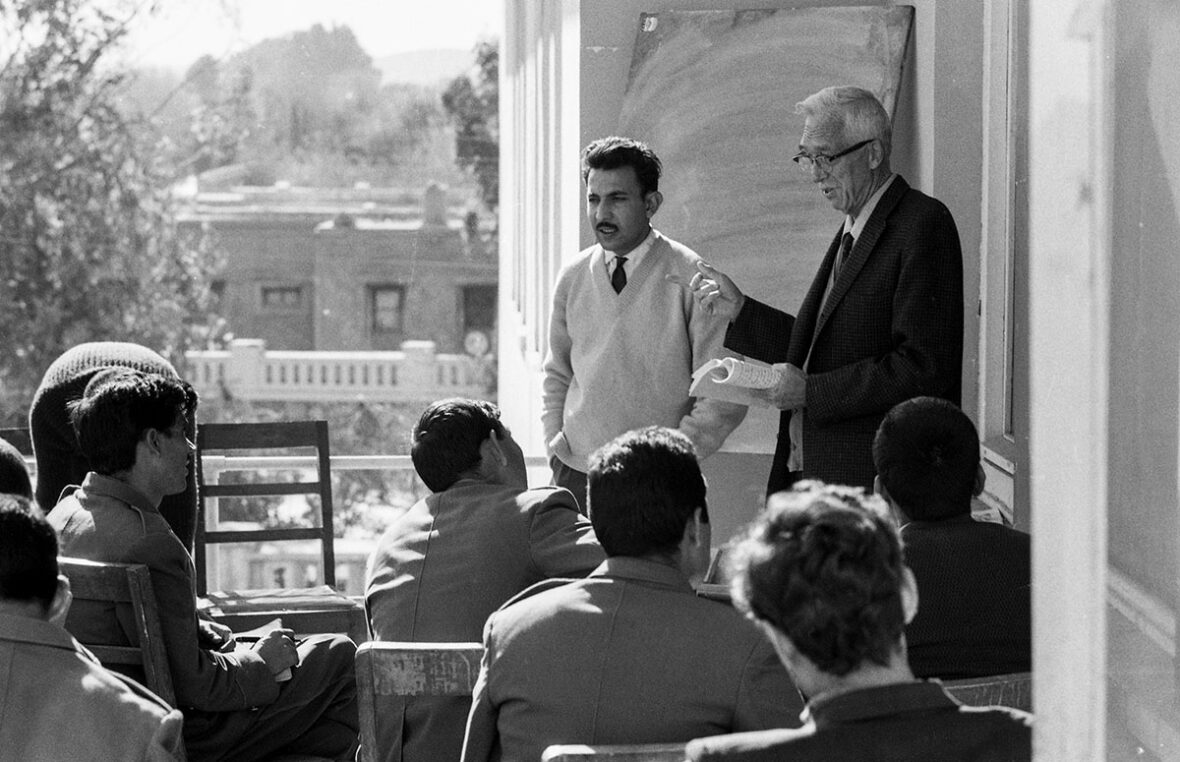

My assignment in Afghanistan was to document a new Peace Corps experiment involving the introduction of medical professionals and their families, instead of the usual selection of recent college graduates. A team of four Peace Corps volunteers arrived at Nangrahar Medical School in Jalalabad in October 1965 to begin the experiment.

The head of the program was Dr. Robert Rodgers, sixty-six, who had retired from a successful pediatric practice in Greenwich, Connecticut where he had also been head of the city’s board of health. His wife, Mildred, was a volunteer serving as a teacher.

The Nangrahar Medical School had been founded three years earlier in Jalalabad. Dr. Rodgers’s job was to help teach students and to train counterpart teachers to gradually take over full teaching responsibilities. He felt it was going to take six to eight years to accomplish.

“There are also three volunteer laboratory technicians and a chemist. This year two more physicians from the Peace Corps joined us: one in surgery, one in medicine. All the doctors are married, with seven dependent children.” This was a very unusual condition for the Peace Corps. “They are essential to the program as we plan to train more in-country technicians to carry on. Eight volunteer nurses train Afghan student nurses and organize the hospital nursing service as well as creating new community health stations in the preventative medicine department.”

In addition, there was a volunteer pharmacist developing a department of pharmacology, four volunteers taught English to the students and the program provided two volunteers to fill two other much needed functions; teaching general science and serving as a secretary-librarian.

“The job should dictate what supplies and what transportation are needed. Peace Corps Volunteers are allowed to have bicycles but not vehicles.” Distribution of these tools, Dr. Rodgers felt, should not be governed by preconceived ideas by bureaucrats in Washington.

According to Dr. Rodgers: “If the Medical Volunteers cannot function efficiently there is the almost certain danger that the program loses its effectiveness and host countries will no longer require its services. We’ll fade out of the picture. We must have vigorous and understanding support for the people who might be characterized as different volunteers.”

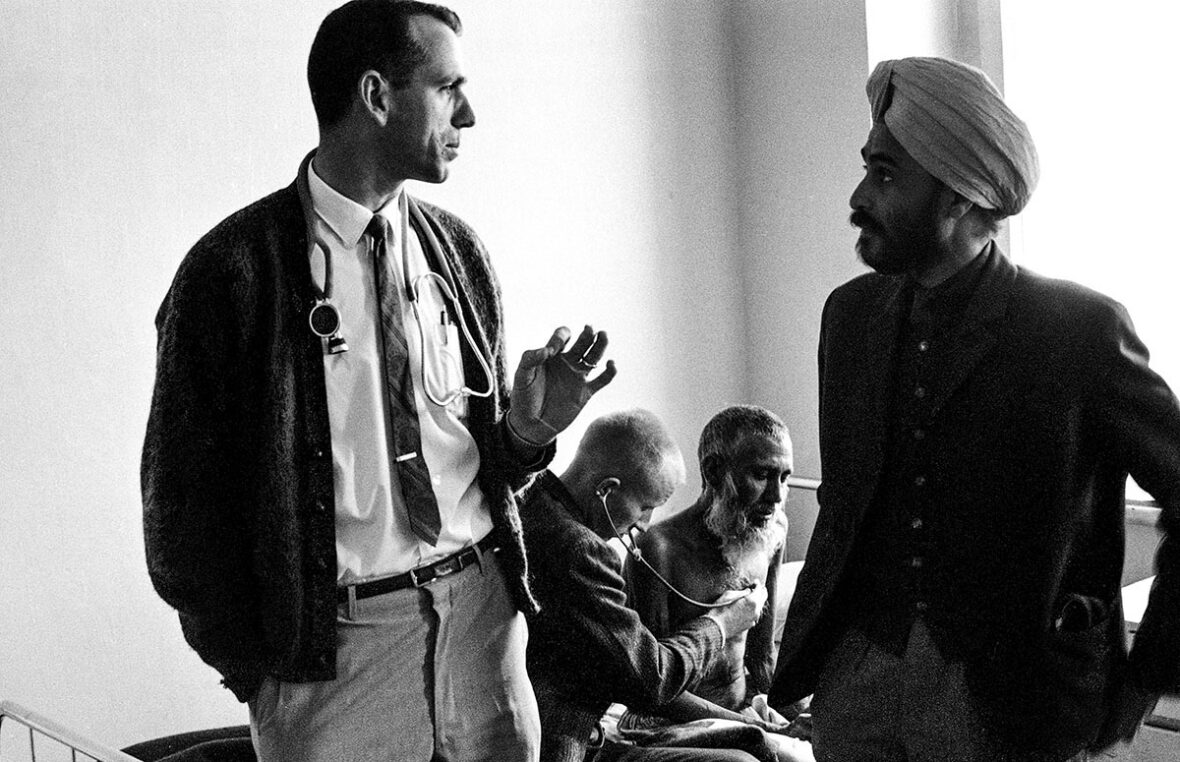

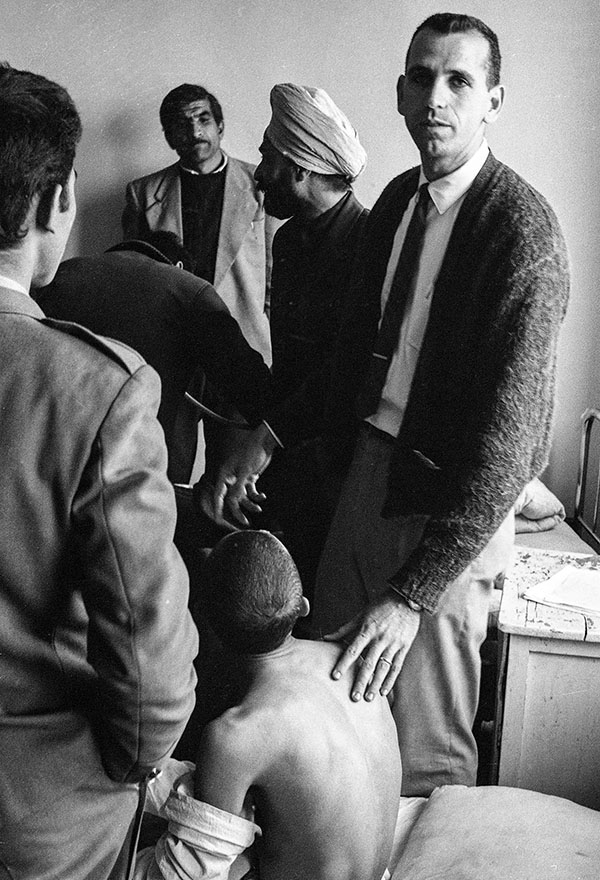

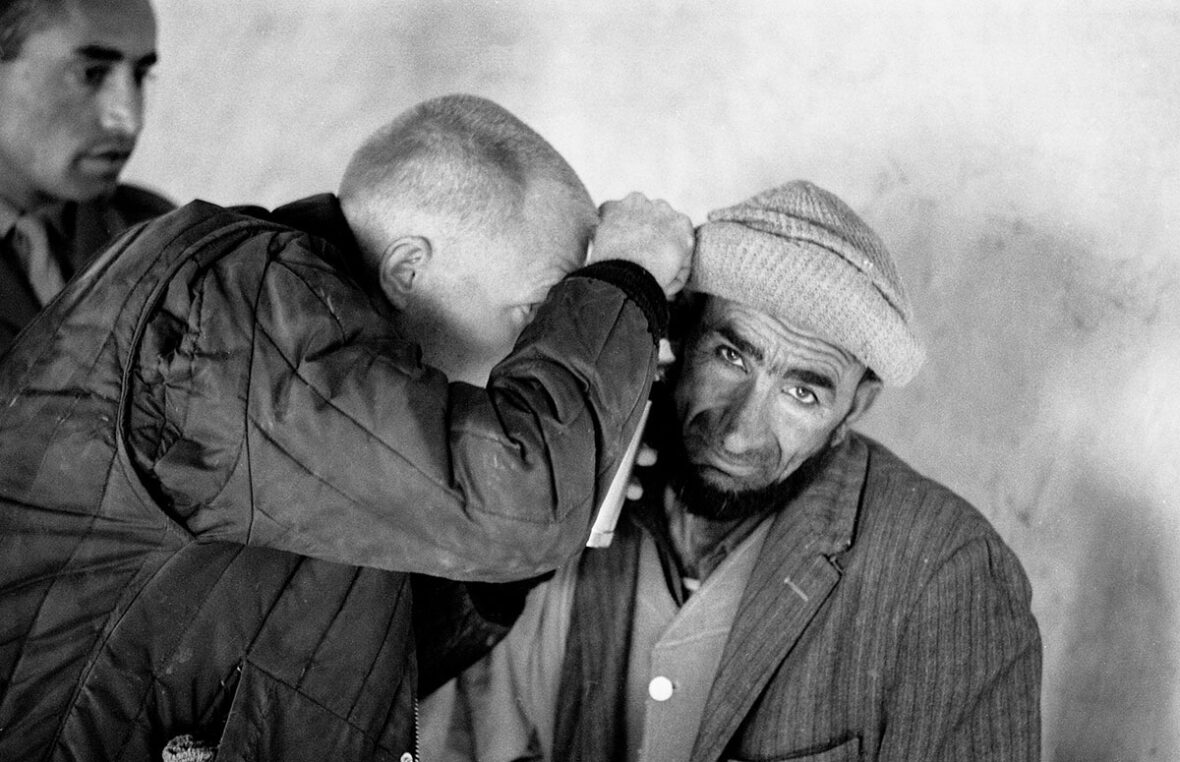

Peace Corps doctors knew what they were doing in detail. They worked toward a plan that was sensible and possible. There was an amazing interaction between Peace Corps volunteer doctors and their Afghan colleagues, assistants, and translators.

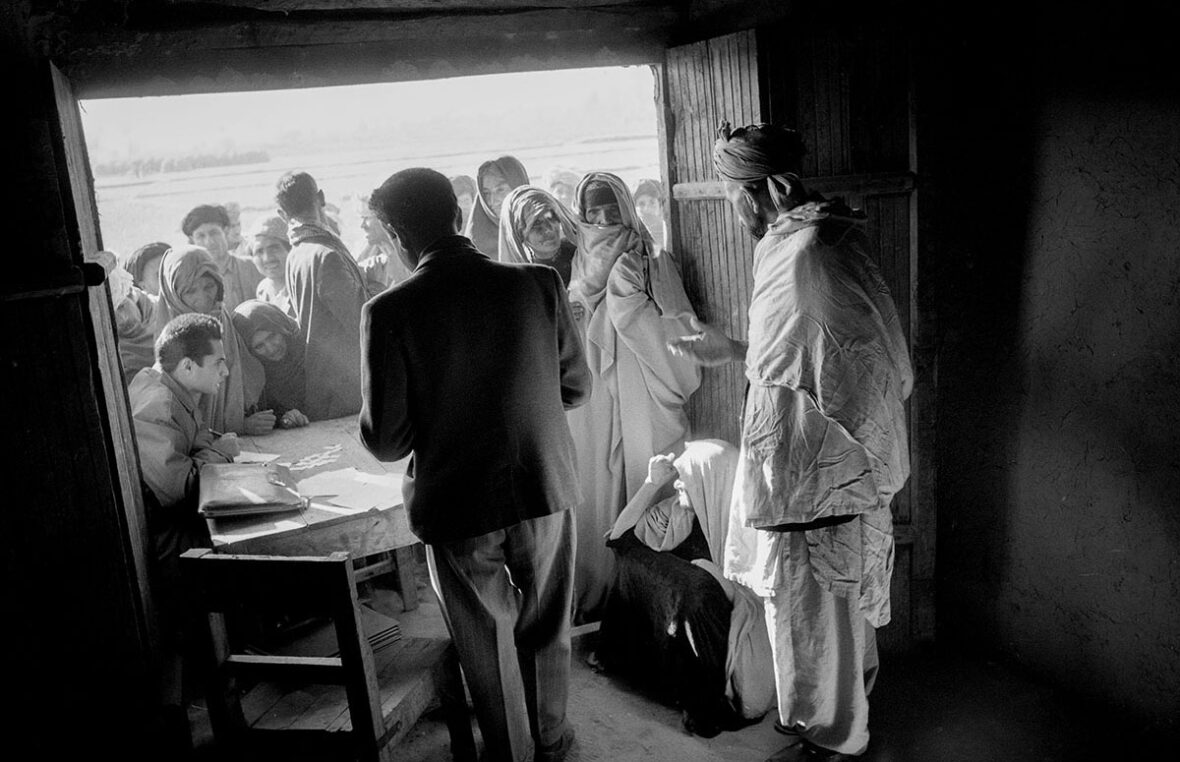

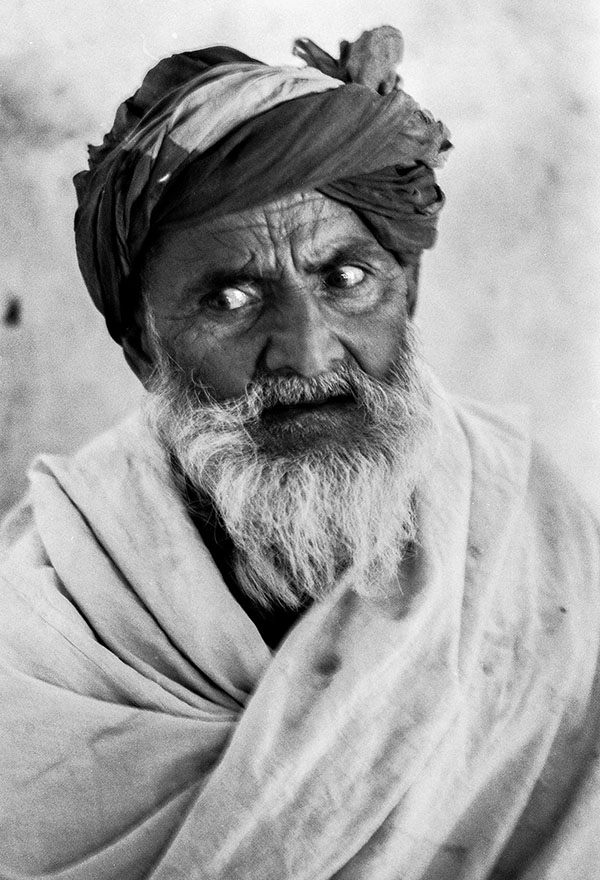

Swarms of women pressed against the window of the hospital to get cartons of “Nonfat dry Milk” “DONATED BY THE PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA”. Some were clutching their babies. Forty to fifty children were examined every day for respiratory infections, diarrhea, parasites and other problems. The women’s expressions ranged from anxious to aggressive. None were veiled. Where did strict rules about veils stop and start?

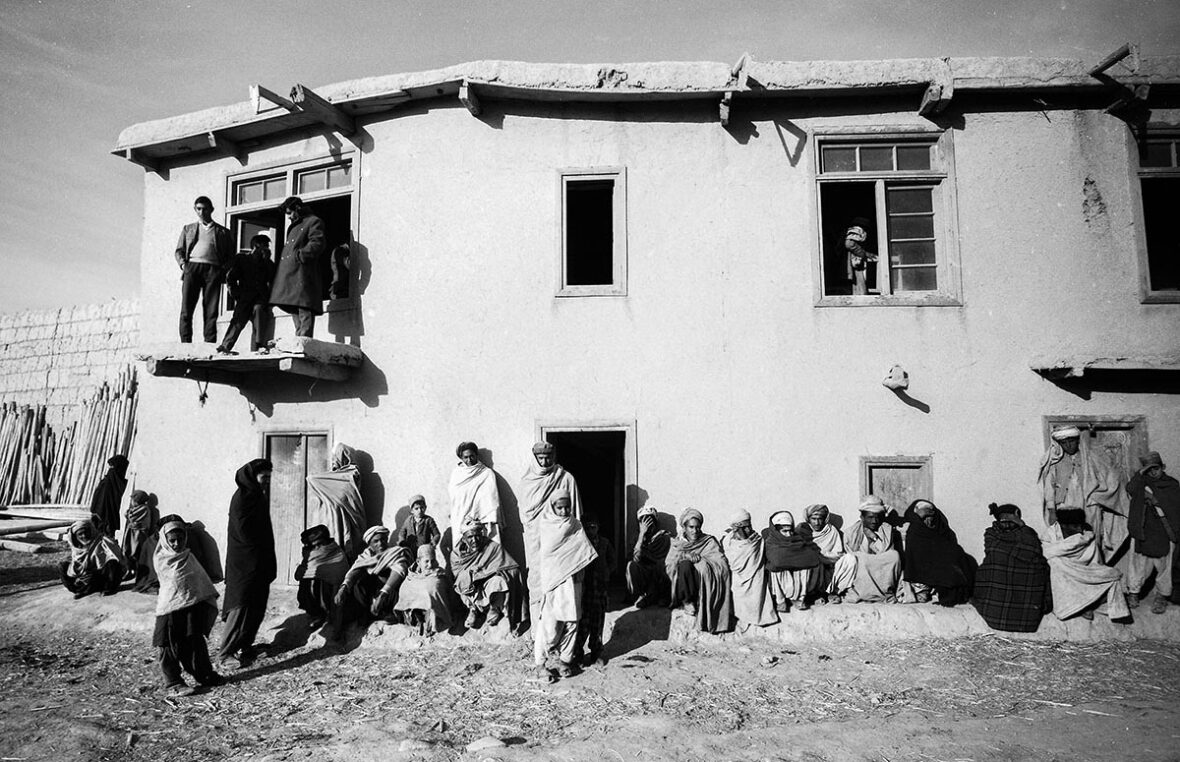

Jalalabad’s Nangrahar Hospital and the rural clinics in the village of Hesarshaie and Madrawal were the places where Americans and rural Afghans met on an intimate basis bringing together two worlds that were so different that it is almost impossible to see how they could understand one another.

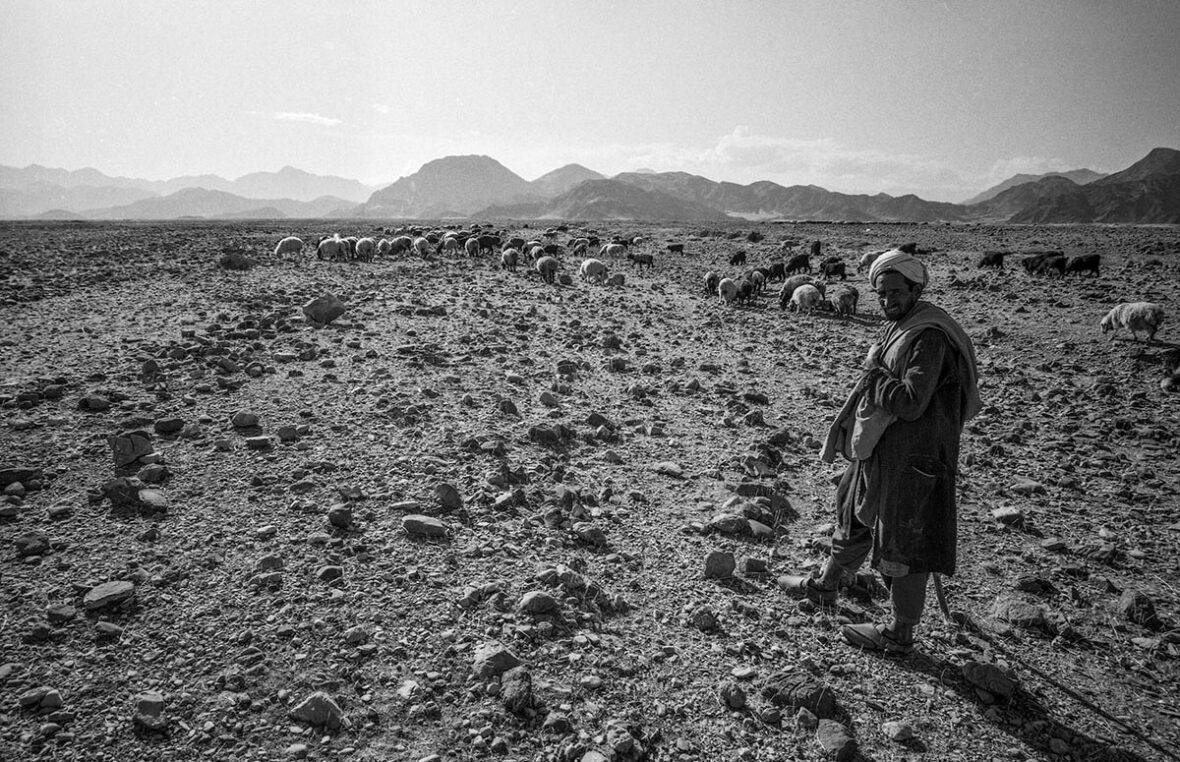

The two village clinics, operated by the Peace Corps, gave me a chance to observe the intimate contact between Americans and village Afghans. I worked in Madrawal (population 4,000) which had one of the two village clinics. It was a 45-minute trip over a desolate rocky road from Jalalabad.

The Peace Corps Jeep took me over a sloping trail that stretched over utterly desperate land between thrusting ranges of intimidating rock that seemed to cut off anything that might encourage life. These stretches seemed to be filled with the shrapnel left over from a war that the mountains were having with themselves. There was nothing soft here nor was there a blade of grass, a tree, or animal in sight; nothing until we finally found a sheep herder, standing with his animals.

The clinic in Madrawal seemed to be shared by animals on the outsize as well as people on the inside. The rooms inside were sparsely furnished, but provided a place to examine old and young, men and women. From here the seriously ill were moved to Nangrahar Hospital in Jalalabad.

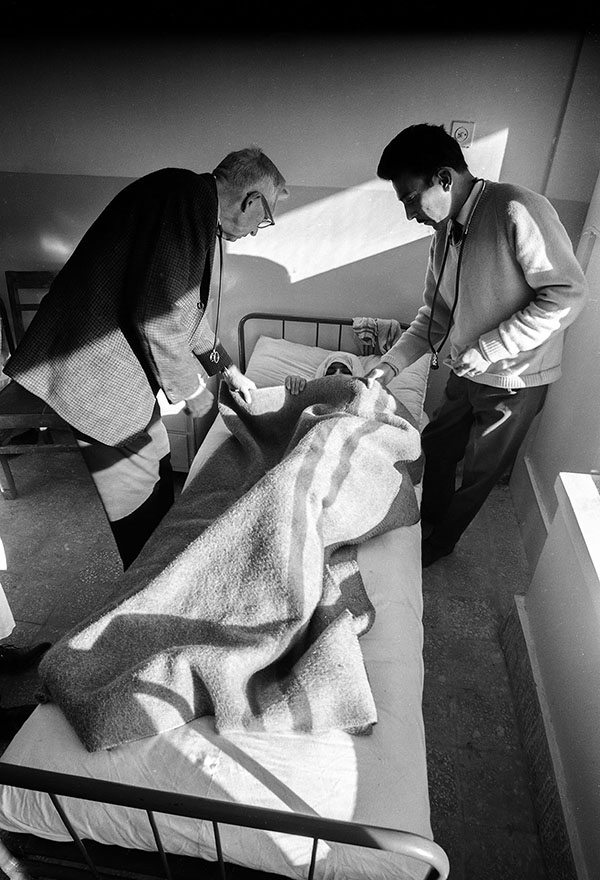

Newly arrived PCV doctors Charles Kelly and Dennis Hamilton, examined patients in Madrawal where the only light was provided by the sun. There was no electricity in Madrawal

After three months in Jalalabad, I began to sorting out what I had learned from my experience with the Peace Corps doctors. From a visual point of view, I had been treated to life-saving interventions with Dr. Rodger’s and his Peace Corps and Afghan team. This was a dramatic record of what can happen when Americans with advanced skills are able to help alleviate punishing medical conditions but the experience, for me, was like viewing Afghan life with a flashlight, illuminating what I could. What I saw was overwhelming, but the lit spots barely hinted at the vivid complexity of Afghan village life.

When it was time to leave, I flew out heading home. At 20,000 feet, I had one last look at Afghanistan as I passed over rows of sharp edged mountains – dozens of them extending to the horizon. Mountains have always stimulated my imagination. Perhaps they reference my childhood in Switzerland and the ice axe in the attic that belonged to my father who used it climbing when he served there as a diplomat.

These mountains in Afghanistan spoke to the challenges that President Kennedy had in mind when his brother-in-law, Sargent Schriver created the Peace Corps. But today, these mountains have become barriers to many such dreams. Locked between them are furious questions and devastating events. In In 1966 I couldn’t have imagined that the gateway to Afghanistan would be marked again by war and foreign intervention – closing the Khyber to me and so many others.

The life-saving work that I recorded in Jalalabad with Dr. Rodgers and the Afghan team in Jalalabad in Nangrahar Province and Madrawal would be erased by current history and new military incursions in Afghanistan. A recent news broadcast became personal when a U.S. drone strike was said to have successfully killed terrorists in Nangrahar province.